1- You are laying down on the bed with her and she talks about all her calamities and the sufferings she has faced in the past few years. You say nothing and look at her tattoos while listening to her. Other than these tattoos you’ve only ever been this close to the tattoos of your grandmother. Your grandmother had them as a tradition, not a conscious choice to manifest any sort of anything. You could probably find the same tattoo patterns on the hands of every woman of her generation, where individuals would find their identities in what they have in common. But now, for you, her tattoos are unique. You could only find them on HER body, and this uniqueness makes her more precisely visible to herself and to you. You can guess her delicate, sensual personality from the tattoos. She is grateful that you didn’t give any input on her life story. You just quietly listened to her as a wall does. Only after she mentions that you were quiet the whole time, you feel a deep desire to speak, to say that you are sorry. But even being sorry is too much. People are often sorry, when they don’t deeply understand the pain and make a lame attempt to contribute.

2- One of those long and hot Seattle days.

She reserved a sauna for you both. For you and her, prior to Seattle’s decision to be hot. So you couldn’t excuse yourself. Before she spoke of the back surgery she had before, and the big stitched scars on her belly as well as her back, about how uncomfortable she was feeling because of those marks but slowly she was overcoming her dis-ease.

In the sauna, you saw her scars for the first time. A big interruption to a standard beauty. Your eyes go over the scars as easily and indifferently as they went over the body of a dead donkey along the roadside, years ago. But in fact, each time you pretended that you didn’t see anything, didn’t notice something, you couldn’t forget about it later. You don’t forget her sophisticated confidence and you don’t forget the shape of the dead donkey’s mouth, curling around the foregone death rattle.

In the sauna she chose the pool with depth and it covered her scars and her belly. Is it a conscious decision? Or are you only conscious when you are stepping out of the arena? You get dehydrated from the heat and go upstairs, keeping yourself busy around a chess board, hoping she can enjoy the sauna with two less eyes on her misery.

3- Ankara, Turkey.

Outside is freezing. Inside you are all sitting on uncomfortable couches only ownable by refugees– If, in this case, “owning” is the correct word to describe such relating to objects.

You don’t exactly remember how your discussion arrives there, that she starts talking about her experiences in prison, post-revolution. How she was treated in prison. Her husband was executed in prison and she gets tortured for months.

She gives birth in prison, and her daughter starts her life with people who have been sentenced to death. Her whole body is covered. Her socks are always on. Is it because she doesn’t want you to see the scars? But you can imagine the marks from the cables, everywhere, on her body and on her feet. You feel even her shadow has scars. Only when she dances or when she is cooking do the scars disappear.

You are frozen from inside and you go out. You don’t feel the cold anymore maybe because you feel colder inside. Often, you cannot hear about someone’s pain without feeling it in you, in your body. You feel your legs hurt from the cables which whipped her legs forty years ago. You cannot move your legs. You left a hallway door open and now you cannot go inside to close the door. But she can only sleep when the door is open and the lights are on.

4- You are on the beach in Den Haag.

The sun hovers in the middle of the sky in such a way that you are reminded of the hovering of your elementary school teacher and how he would dictate correct Farsi spellings.

You couldn’t escape his gaze except to continue writing in the hopes of finding the correct spellings.

You have your favorite glasses on and you’re not aware of losing them a few months later, on November 9th in train number 8651 headed for Schiphol around 10:20 in the morning, while being busy thinking about someone. You keep your glasses on the whole day as if to make up for the time after you’ve lost them, putting them to good use.

She joins you later in the afternoon. Everyone is going in the water except you. You cannot leave your thoughts alone on the beach and enter the water without them, so you decide to stay. One person always has to stay behind. Beneath the glasses it is easier to watch people undetected. One of your hobbies is imagining being them.

Suddenly you are pulled from watching people as she moves in your periphery. She is struggling with covering her big scar. Later in the evening, when its dark and honesty is less hesitant and shy, she talks about her insecurity about her scar. Does she need comfort or affirmation? Or does she just need to shout out about the eternal scar shouting itself vertically across her abdomen? You don’t say anything. You don’t say sorry. Or anything.

You want to mention that scars are perfectly fit to their mission, they might or might not sit in your insularity, that’s all.

5- You just read an article about the anthropology of pain. A portion of the article touches on tattoos and their relationship to pain. If you remember correctly, it also talks about capitalism and the embodiment of power structures—even in the bed, in your most intimate exercises. It makes sense to you. It also talks about tattooing particular parts of the body and its association with the pain that comes from some sort of systematic or personal experiences of abuse. It also talks about the target demographics and the business surrounding it. You remember when you were a public transit operator in Seattle. Some passengers completely covered in tattoos and piercings. You remember wondering if they believed in change within themselves. They were literally covered from head to toe with permanent clothes that they could never take off. Don’t they hesitate, that who they might be in the future could come to contradict who they are now? Or they will be unchangeable characters in a classic novel, who never change until some twist and turns in the plot of the story? But even those boring stories leave room for regret. There is not even a cubic inch of untreated flesh left, not even a cubic inch of room for regret. The more you read about it the more visible it becomes to you, the more you see the tattoos on passenger’s bodies. It becomes an interesting subject to you but you cannot find enough attachment to the concept to compliment them on their body art. You feel your appreciation would be fake. To make a comment would be empty.

You deem it a modern phenomena, although it has been around for a long, long time. You wonder just how personal a personal choice is.

6- She just recently changed medications and she’s worried about the side effects. You’re worried about her too and you wish you could do something. “There is not much you can do when your enemy argues within your body and feeds itself with whatever it wants from within”, This is more or less what she says.

You must feel it to call it pain. You also think of the silent pain. You supposed it is when you got the idea of working with something related to scars and tattoos.

7- You ask in the group chat if anyone has a scar or tattoos they would be willing to have filmed. You are especially interested in scars and tattoos that people are uncomfortable showing. She responds to you immediately. It’s been a year that you know each other but you’ve never had the chance to talk more than surface interactions. She doesn’t fit easily in any particular box. Everything with her goes smoothly, she directs herself and decides where to go and what to do next.

It is where you decide to ask her to cover her tattoos with lipstick.

8- You show the first drafts of your work. The whole time, she’s been sitting on a chair in such a position that only an older person would know that she won’t be able to sit that way for even ten minutes ten years later, when your joints start rubbing against time.

She asks you if you knew that one way to hide a tattoo is to cover it in lipstick first and to then apply concealer.

You didn’t know that, but you find it very relevant to your work.

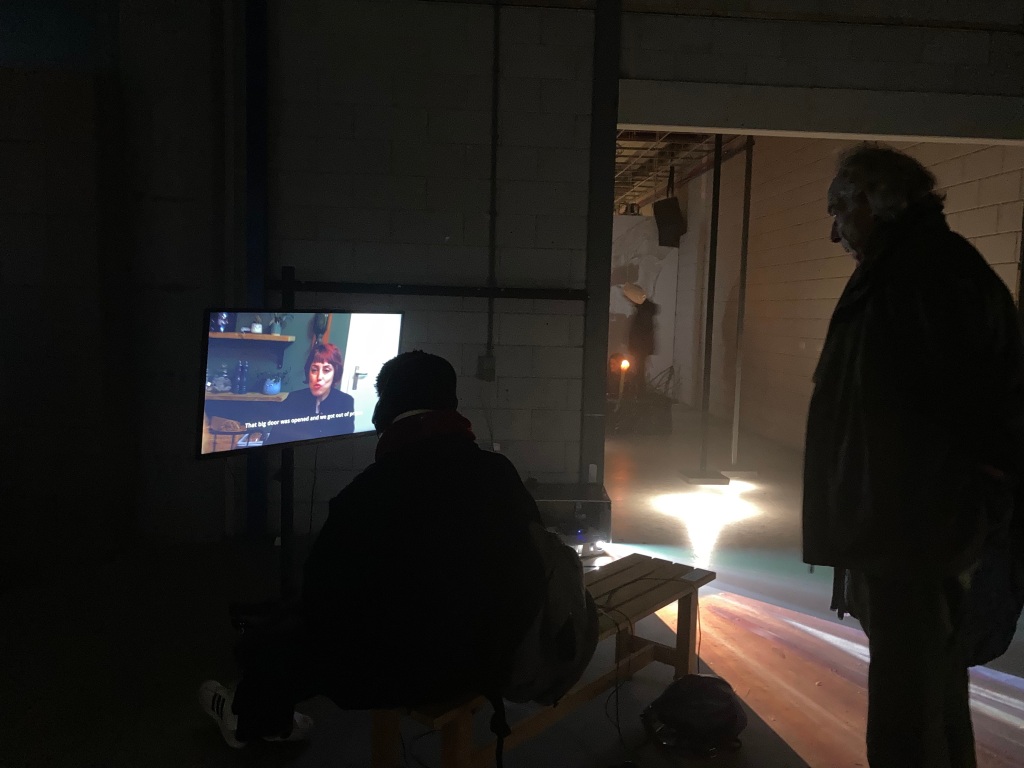

9- It is an installation. The water is dripping from the ceiling into bowls and glasses and being recorded by a contact mic. The work is about multiple sclerosis, MS, and you are fascinated by the recording and the concept that is not unrelated to yours. You ask her for permission to use the audio and she graciously accepts.

10- You read the line of a poem written by Paul Eluard transited from French to Farsi.

For a moment, you are frozen.

How could he find those words and put them in that order?

How is it possible to use these words in this way to convey this deep, deep meaning?

You ask all the French speaking people you know if they can help you in finding the original line. No luck.

The rough translation of this line becomes the inspiration for this project:

“Give them a stabbing

deeper than insular seclusion.”

Jenny- “Something sitting in the back of my throat.

Iseeyouiseeyoyi[dont]see [myself]younotseeingme…”

Fanny- “I am

human by default,

because if I could choose,

I would get rid of the guilt,

the judgment,

morality,

anxiety,

greed,

arrogance,

pride

and pity…”

Romana- “Pain doesnt come only from outside, sometimes pain sleeps with you. It sleeps underneath your skin through all these years, invisible for everyone, for you…”

Jenny- “And when I force myself to be, how much of me is me and how much is drowning in this ,you’? Something sitting in the back of my throat…”

Fanny- “Can I exit my existence for the unconscious being ?

The so fragile flower,

that its life hangs on its beauty;

An anchored tree,

which provides shelters and life to others;

A rock,

shaped and unshaped by the flowing time…”

Romana- “My body eats itself. I can’t remember how my body feels without pain, when my legs were not shaking, breaking on stairs, when my hand could play violin, unheard melodies, untold stories, … I don’t play anymore…”

Jenny- “with fleeting moments less and shrinking and vanishing until the ,what is feeling’ and to ‘recognising a reflection’ but not seeing anything…”

Fanny- “Away from romanticism ideals

each one of the living has some killings on its bag.

But of all the species, humans are the ones we can’t excuse…”

Romana- “I can’t recognize signals so everythings is fine. I can’t understand my body, we are talking in differenet languages. We are trying to understand, to listen to each other but life outside is too loud…”

Jenny- “Fury and fury and jittering retching and something that’s been sitting in the back of my throat for years.”

Fanny- “I am tired of these eyes.

Yet they are the only ones.

Be my thoughts drowning with the rain in the ever-changing sea.”

Romana- “You feel that your body is in pain. You feel that your body is yours.”